Extending what is ordinary available to all

Last update: 11/09/2023

- Theme: Inclusive Pedagogy

- Media:

Dr Tracy Edwards is a lecturer in Special Education, Inclusive Pedagogies and Digital Learning at Leeds Beckett University. In this blog, she explores the notion of 'extending what is ordinarily available to all' which is central to the academic literature on Inclusive Pedagogy (e.g., Florian, 2015).

Inclusive Pedagogy is an approach to teaching all learners (Florian 2015). It is an alternative to approaches to classroom practice which plan activities deemed suitable for “most” learners, alongside “additional” or “different” activities for “some”(Black-Hawkins and Florian 2012). Inclusive Pedagogy starts with the notion of “everybody” and asks us to consider how we can enhance the overall offer of learning to everyone, before placing pupils in “ability groups”.

The implementation of Inclusive Pedagogy therefore starts with “extending what is ordinarily available to all” (Black-Hawkins and Florian 2012, p. 575).

How might a teacher “extend what is ordinarily available to all” within their classrooms? Below, are a few examples that have been explored by teachers as part of the “proud to teach all” project.

Example One: ‘Warming Up’ a text

“The cost of hiring a paddle boat is £6.50 for the first half hour and £2:00 for each half hour after that. Priya and her friends would like to hire a boat. They have £20 between them.

How long can they have the paddle boat for?”

‘Warming Up” a text involves preparing pupils for what they are about to read, before presenting them with it. Warming-Up the above Maths word problem, for example, may involve spending 5 minutes talking through the below PowerPoint slide with pictures of a “paddle boat” a £20 note, and of “Priya” and her friends. In doing this, terms which not all students are familiar with could be introduced such as “hire” and “paddle boat”. Alternatively, a teacher could use physical objects to represent some of these terms.

By “warming up” a Maths words problem, it is likely that a higher proportion of pupils will access it, reducing the requirement for a teacher to plan different simultaneous activities for different perceived “ability groups” within her classroom. Rather than carry out the exhaustive task of sourcing different worksheets for a lesson, there is also scope for the teacher to adapt the activity responsively and informally (for example by giving pupils the option of reducing the cost of hiring the boat to £5:00).

Example Two: Applying ‘Autism Friendly’ approaches to all learners

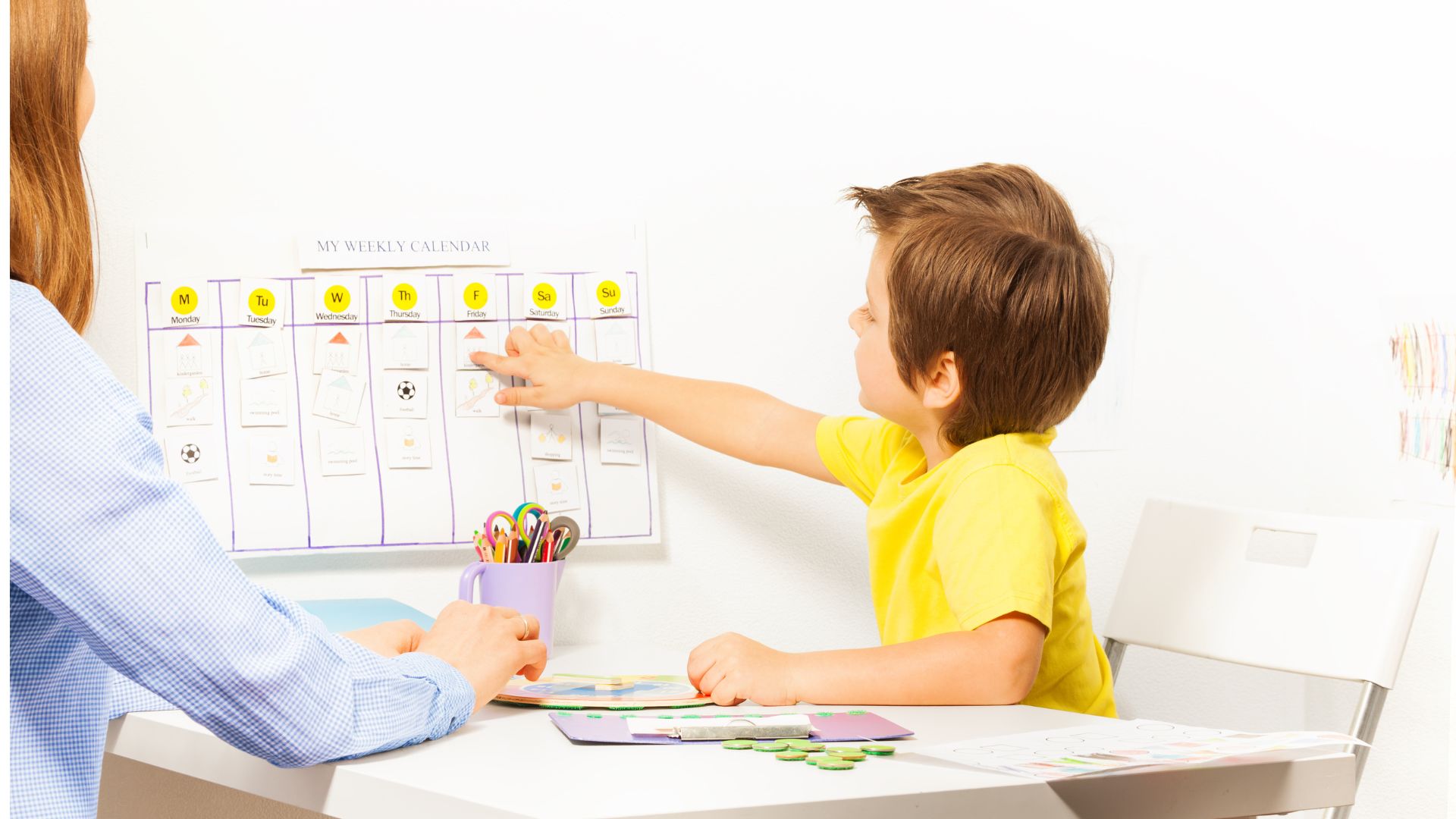

Visual timetables within a classroom outline the sequence of a school day and/or the sequence of activities in a lesson. They are associated with autism education, and often seen as a specialist intervention for those with an autism diagnosis. For some, a visual timetable may be supported along with Now/Next boards which outline for a pupil what is going on “now” and what they will be moving on to do soon (see examples below).

In my own experience as a teacher, visual timetables can benefit all children and young people in schools and does not only benefit those diagnosed as autistic. The research on waiting times for a diagnosis (Crane et al. 2018; Kelly et al. 2019) and on the imperfections of the diagnostic process (Crane et al. 2018)suggest that autism may be a barrier to participation and learning in many lessons, for many more children and young people within our classrooms, than we might initially think. Visual timetables are also likely to support pupils with attention difficulties, difficulties with working memory, or the “time-blindness” associated with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Visual timetables can also work to resolve the anxiety that we all might feel, when unaware of the direction our day is going. I know that personally, whenever I go to a meeting, I like to first have an agenda, or see a flipchart with a plan of the day on the wall.

One teacher I once worked with, taught teenagers in an Alternative Education setting in England, for pupils who had been excluded from other schools. None of the pupils in his class had a diagnosis of autism yet benefited from having a visual timetable on the wall. Although this visual timetable was contextually appropriate and looked very different to those in the above pictures (and was often a PowerPoint slide printed onto A3 paper) the principle behind its use was exactly the same. When looking at specialist strategies associated with particular special educational needs, I have found, it is often helpful to consider how they might be channelled to “extend what is ordinarily available to all” pupils rather than be seen as remedies in relation to individual pupils.

Example Three: Using concrete manipulatives across the age-range

Concrete manipulatives are physical objects which we work with and handle. In Mathematics education, an example of a concrete manipulative might be a sets of toy sea creatures to count, or ‘base-ten’ sets to enable pupils to count in 1s, 10s and 100s. Concrete manipulatives are commonly found in early years classrooms. In my experience however, they tend to be used less in upper primary and secondary settings.

Building a positive culture around the use of concrete manipulatives with older learners, across all curriculum areas, is one way of “extending what is ordinarily available to all”. This can include the use of artefacts in History and Religious Education for example, or the use of model making kits to enable pupils to emulate the interactions between sub-atomic particles in Science.

Although offering different activities for “some” learners, some of the time, may still be a necessity, a “subtle but profound shift in thinking”(Florian et al. 2010, p. 712) away from “most” and “some” enables us to see beyond perceived deficits in individual children and focus on education for all. It therefore supports a “more optimistic view of human educability” (Hart et al. 2004, p. 11).

BLACK-HAWKINS, K. and FLORIAN, L., 2012. Classroom teachers craft knowledge of their inclusive practice. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, vol. 18, no. 5, [Available from: DOI 10.1080/13540602.2012.709732].

CRANE, L., BATTY, R., ADEYINKA, H., GODDARD, L., HENRY, L.A., and HILL, E.L., 2018. Autism Diagnosis in the United Kingdom: Perspectives of Autistic Adults, Parents and Professionals. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 48, no. 11, [Available from: DOI 10.1007/s10803-018-3639-1].

FLORIAN, L., 2015. Inclusive Pedagogy: A transformative approach to individual differences but can it help reduce educational inequalities? Scottish Educational Review, vol. 47, no. 1.

FLORIAN, L., YOUNG, K., and ROUSE, M., 2010. Preparing teachers for inclusive and diverse educational environments: Studying curricular reform in an initial teacher education course. International Journal of Inclusive Education.

HART, S., DIXON, A., DRUMMOND, M.-J., and MCINTYRE, D., 2004. Learning without Limits. Place: Milton Keynes . Publisher: Open University Press.

KELLY, B., WILLIAMS, S., COLLINS, S., MUSHTAQ, F., MON-WILLIAMS, M., WRIGHT, B., MASON, D., and WRIGHT, J., 2019. The association between socioeconomic status and autism diagnosis in the United Kingdom for children aged 5–8 years of age: Findings from the Born in Bradford cohort. Autism, vol. 23, no. 1, [Available from: DOI 10.1177/1362361317733182].

Related Materials:

In 24th August 2023, an event took place to mark the end of the Erasmus+ 'Proud to Teach All Project' and celebrate its successes. This event included dialogues on inclusive education involving teac…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

The Belgian NationalTV (VRT1) came to visit and made a documentary in the partner school in Porto to show how inclusive education in Portugal works. How does the school convey that diversit…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

‘Inclusief’ is a feature-length documentary, directed by the renowned Belgian filmmaker, Ellen Vermeulen. It is a movie which captures the experiences of the Flemish school system of children and yo…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

‘Inclusief’ is a feature-length documentary, directed by the renowned Belgian filmmaker, Ellen Vermeulen. It is a movie which captures the experiences of the Flemish school system of children and yo…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

Dr. Annet De Vroey, teacher educator and researcher in inclusive education, talks us through the framework of inclusive pedagogy. How does it strengthen our everyday practice and how does it…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

On the 15th February 2023, the Utrecht University of Applied Sciences hosted an international symposium 'Inclusive Education: What Else?'. The program included contributions from researcher…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

Maren is a young person with special educational needs who attends an inclusive mainstream school. In this episode, Maren’s mother emphasises how effective communication between parents and pro…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

In this podcast two Dutch students talk freely about their ideas around the question: what does a perfect classroom look like? This perfect classroom is discussed from different perspectives. Exa…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

Ebanur is finishing up her masters in Disability Studies at the University of Ghent. As part of her last year, she does an inclusive internship, in which she supports pupils with special needs in…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

Through reflective dialogues in this episode, a history teacher, social pedagogue and psychologist from Oskara Kalpaka secondary school in Liepaja (Latvia) establish shared values for inclusive e…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

In this podcast, Manuela Sanches Ferreira, a Portuguese Coordinator Professor and the Coordinator of the Centre for Research and Innovation in Education, with extended knowledge and experience in…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

In this podcast two students of Hogeschool Utrecht talk about inequality of opportunity or: how do we offer students optimal opportunities that fit their talents? And what does this require from …

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

Inclusive Pedagogy starts with a commitment to ‘extending what is ordinarily available for all learners' (Black-Hawkins and Florian 2012, p. 575). This is unlike other pedagogical responses to le…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

The body of research literature on inclusive classroom practice gives insight into possible ways in which inclusive classroom practitioners might think or behave. In this video, Tracy Edwards fro…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

For Kristine Niedre-Lathere, the head of the municipal education department for the Latvian city of Liepaja, it is important for schools to embrace diversity, and be resourced to work with it. …

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

Inclusive pedagogy gives a framework to recognise the ways in which teachers make school and learning accessible for all. It also helps us keep focus in taking the next (small) steps…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

In this blogpost, Dr Tracy Edwards from Leeds Beckett University, uses the metaphor of 'topography' for inclusive teaching This may seem a funny question. You might even be asking yourself wha…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

Hans Schuman left his post at Hogeschool, Utrecht in June 2021, to begin his retirement. In this episode, he talks with Peter De Vries, a lecturer at Hogeschool, about his career in researc…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

The South African concept of ‘umbutu’ emphasises the mutual interdependences between human beings and how it is through our relationships with others, that we construct our sense of identity…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

Inclusive practice in education involves working with and listening to others. Through this we challenge our own assumptions, and see alternative ways of interpreting what might be going on in a…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

In this video, Rachel Lofthouse, Professor of Teacher Education At Leeds Beckett University in England, talks with two inspiring head teachers, who are committed to strengthening inclusion in sch…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

Tracy Edwards, Lecturer at Leeds Beckett University in England, explains the term ‘bell-curve thinking’ in relation to education. In doing this, she emphasises the importance of rejecting ‘bell-…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

Belgian primary school 't Zwaluwnest introduced a new reading method a few years ago, called LIST (Reading is fun). They read every day for about half an hour, pupils chose their own books and wa…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

The Belgian primary school De Klaproos focuses on helping pupils grow towards independence and responsability. But they wondered, do we really succeed in doing this? And what do our pupils t…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

Following a successful career in school leadership, Cathy Gunning is an educational consultant with a specialism in early years and the inclusion of children who have experience of being car…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

On 22nd March 2023, an event was held with staff working at the schools that are part of Gosport and Fareham Multi-Academy Trust in England. The event was attended by teachers, learning mentors, …

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media:

On 10th May 2023, an event was held at the Department for Education in Brussels, which brought together teachers, school leaders, policy makers, parent advocates, multi-agency professionals and a…

Thema:

Duurtijd: 0- 0min

Media: